Basic concepts¶

This part of the documentation targets to the basic architecture behind ViUR, and describes how the system is made up and how things work together. Those who are new to ViUR and want to write applications with it, should start here.

Overview¶

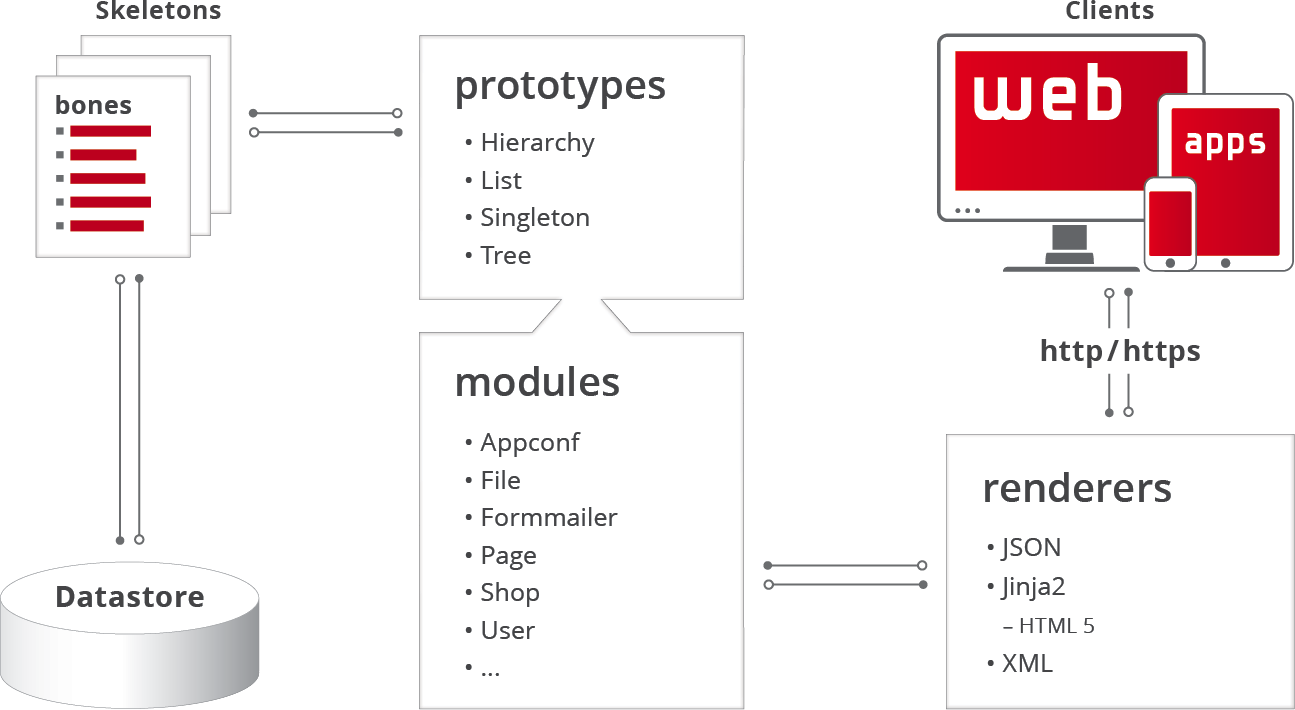

On the first view, ViUR is a modern implementation of the traditional Model-View-Controller (MVC) design pattern. But ViUR is also much more. It helps to quickly implement new, even complex data models using pre-defined but highly customizable controllers and viewers.

The model-view-controller concept of ViUR.¶

The graphic above shows the different parts of the MVC-concept and their relation to each other. Let’s section these three parts of the MVC-concept and explain them in the terms of ViUR.

In ViUR, the models are called skeletons.

As seen from the biological point of view, a skeleton is a collection of bones. Therefore, the data fields in ViUR are called bones. Bones have different specialization and features, but more about that will follow soon.

The controllers are called modules.

They form a callable module of the application, which focuses a specific data kind or task.

To implement modules, ViUR provides four generic prototypes: List, hierarchy, tree and singleton. There are many pre-built modules delivered with the ViUR server that implement standard use-cases, e.g. a user-module, including login and registration logics, or a file-module, which is a tree (like a filesystem) to store files in the cloud.

The views are called renderers.

They render the output of the modules in a specific, clearly defined way. ViUR provides different renderers for different purposes. The jinja2-renderer, for example, connects the Jinja template engine to ViUR, to emit HTML code for websites. The JSON-render serves as a REST-API and is used by several applications and tools communicating with the ViUR system, including the admin-tools.

These are the fundamental basics of the ViUR information system. It is now necessary to get deeper into these topics and arrange these three parts to get working results.

Folder structure¶

A typical ViUR application has a clearly defined folder structure.

This is the folder structure that is provided by the viur-base described in the Getting started section.

project (deploy-folder)

├── app.yaml

├── cron.yaml

├── emails/

├── html/

├── index.yaml

├── main.py

├── modules/

├── skeletons/

├── static/

├── translations/

└── vi/

The following tables gives some short information about each file/folder and their description.

File / folder |

Description |

|---|---|

app.yaml |

This is the Google App Engine main configuration file for the application. It contains information about how to trigger the application, which folders are exposed in which way and which libraries are used. |

cron.yaml |

This is a Google App Engine cron tasks configuration file. |

main.py |

This Python script is the application’s main entry. It is project-specific and normally the place where configuration parameters or specialized settings can be done. |

emails/ |

Template folder for emails. Not necessary for now. |

html/ |

Template folder for the HTML-templates rendered by the Jinja2 template engine. |

index.yaml |

This is an configuration file for the Google Datastore describing compound indexes for entity kinds in the database. These indexes are required for more complex queries on data, but will also be discussed later. |

modules/ |

This is the folder where the applications modules code remains. Usually, every module is separated into one single Python file here, but it can also be split or merged, depending on the implementation. |

skeletons/ |

Like the modules folder, this is the place where the skeletons for the data models are put. Usually, one Python file for every skeleton, but this is also only an advise. |

static/ |

This folder is used for static files that are served by the applications when providing a HTML-frontend. CSS, images, JavaScripts, meta-files and fonts are stored here. |

translations/ |

When multi-language support is wanted, this folder contains simple Python files which hold the translation of static texts to be replaced by their particular language. Its not important for now. |

vi/ |

Contains the vi-admin. Vi-admin is an administration interface to access the ViUR system’s modules and its data. It’ some kind of backend for ViUR, but it could also be the front-end of the application – this all depends on what the ViUR system implements in its particular application. |

Note

When a project is created from our base repository, the same structure can be found in the deploy/ folder, which is the part that is later deployed to Google App Engine.

Skeletons and bones¶

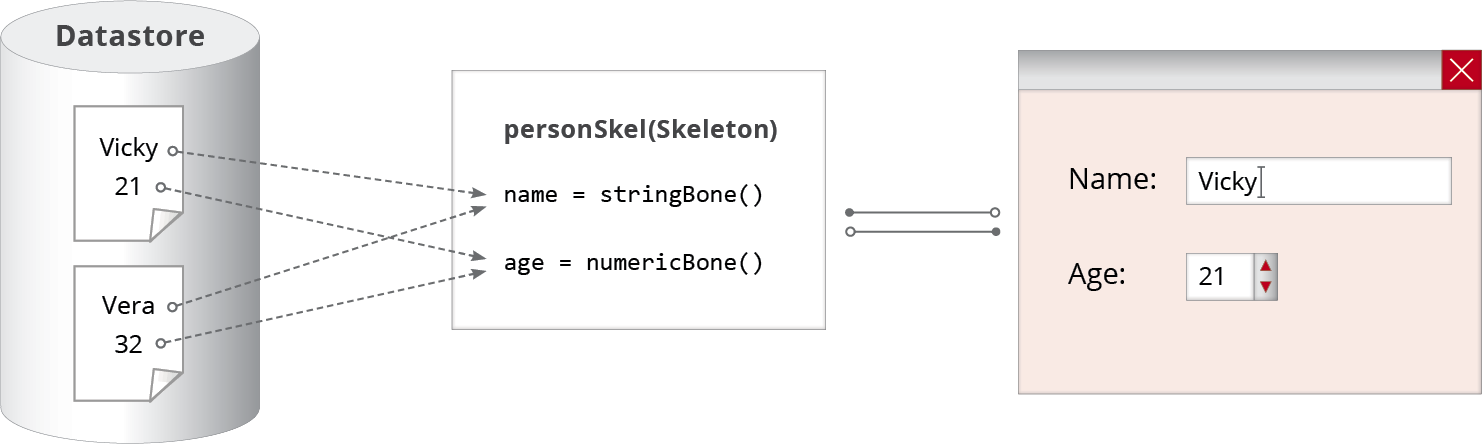

Skeletons are the data models of a ViUR application. They describe, how and in which ways information in the database is stored and loaded. Skeletons are derived from the class Skeleton.

The skeletons are made of bones. A bone is the instance of a bone class and references to a data field in the resulting data document. It performs data validity checks, serialization to and deserialization from the database and reading data from the clients.

Skeletons and their binding to the datastore entity and the user interface.¶

The skeleton shown in the graphic above is defined in a file person.py which is stored in the skeletons/ folder of the project.

from viur.core.skeleton import Skeleton

from viur.core.bones import *

class PersonSkel(Skeleton):

name = StringBone(

descr="Name",

)

age = NumericBone(

descr="Age",

)

That’s it. When this Skeleton is connected to a module later on, ViUR’s admin tools like the Vi automatically provide an auto-generated input mask on it.

A Skeleton does automatically provide the bone key also, which is an instance of the class KeyBone.

This bone holds the value of the unique entity key, that is required to uniquely identify an entity within the database.

The pre-defined bones creationdate and changedate of each skeleton store the date and time when the entity was created or changed.

In terms of ViUR, an entity is a document or dataset in the datastore, that stores information.

By default, ViUR provides the following base classes of bones that can be used immediately:

BooleanBoneforboolvalues,DateBonefordate,timeanddatetimevalues,NumericBoneforfloatandintvalues,RelationalBoneto store a relation to other datastore objects with a full integration into ViUR,SelectBonefor fields that only allow selection of certain key-value pairs,StringBonefor strings or list of strings,TextBonefor HTML-formatted content.

This is only a list of the most commonly used bones. There are much more specialized, pre-defined bones that can be used.

Please refer the bones API reference for all provided classes and options.

Prototypes and modules¶

Modules are the controllers of a ViUR application, and implement the application logic. To implement modules, ViUR provides three basic prototypes. These are List, Singleton and Tree.

Type |

Purpose |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

ViUR comes with some build-in modules for different application cases:

Fileimplements a file management module,Userimplements a user login, authentication and management module,Pageimplements a simple content management module.

By subclassing these modules, custom modifications and extensions can be implemented for any use-case. In most cases, applications make use of custom modules which base on one of the prototypes as described above.

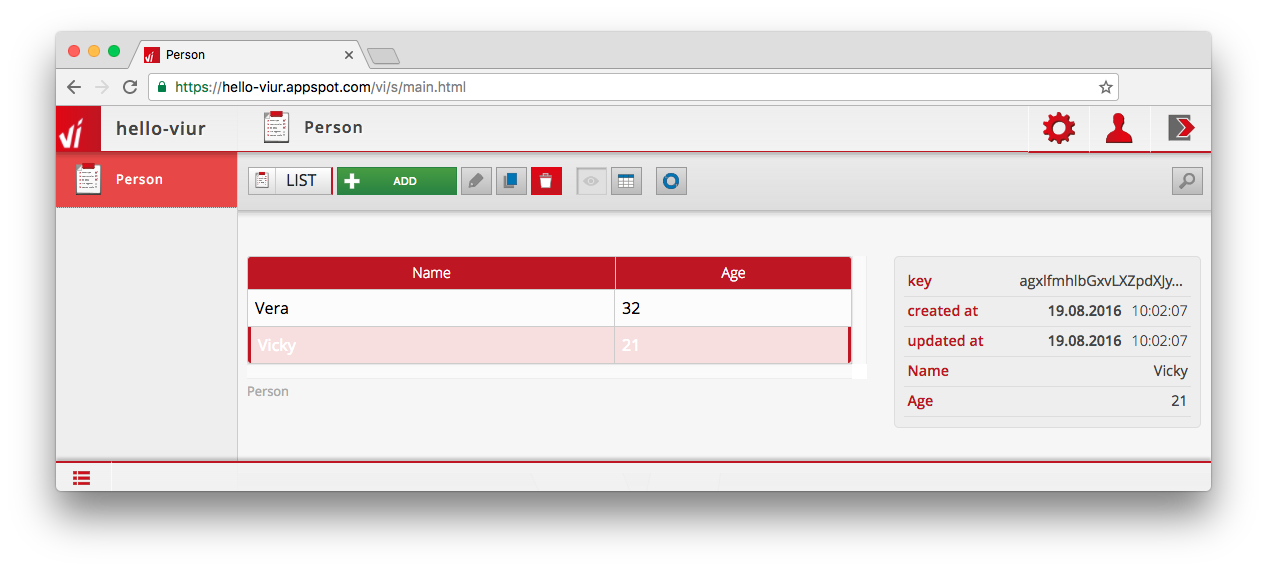

To connect the Skeleton PersonSkel defined above with a module implementing a list, the following few lines of code are necessary.

from viur.core.prototypes import List

class Person(List):

pass

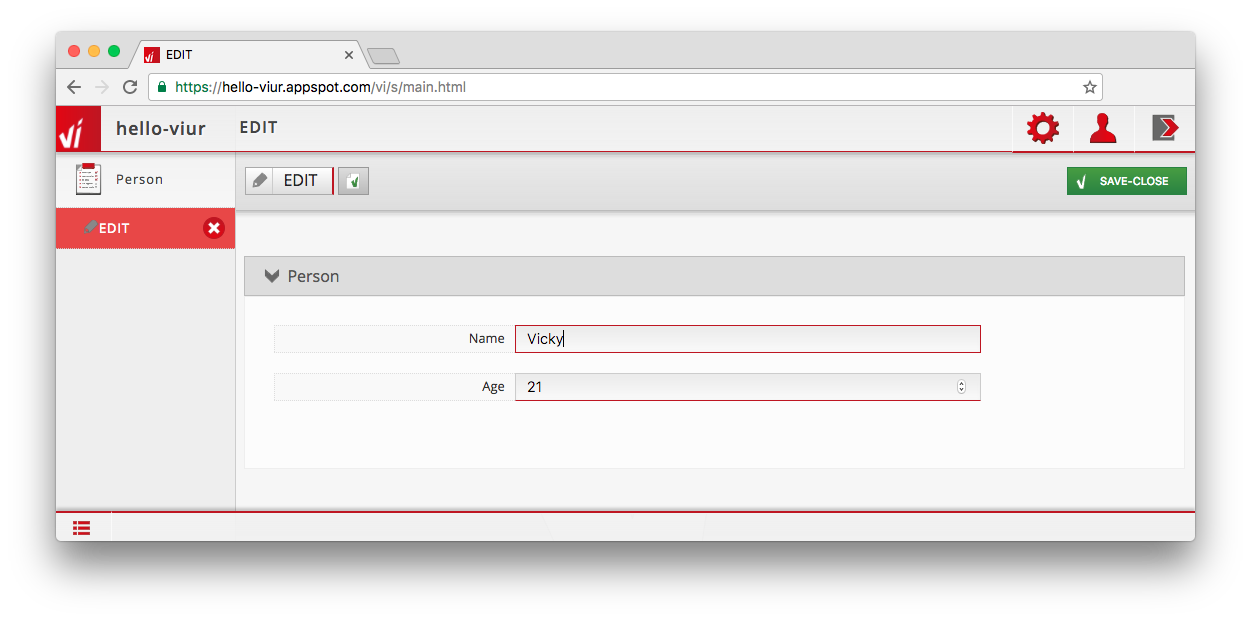

Putting this into a file person.py in the modules/ folder of the project is all what is required to load or save information using the Vi. The screenshots below demonstrate, that datasets are shown using the list module…

…and the input mask is then generated from the skeleton, on editing or adding actions.

Renderers¶

The renderers are the viewer part of ViUR’s MVC concept.

ViUR provides various build-in renderers, but they can also be extended, sub-classed or entirely rewritten, based on the demands of the project.

The default renderer in ViUR is html, which is a binding to the powerful Jinja2 template engine to generate HTML output.

Jinja2 is used because it has a powerful inheritance mechanism, build-in control structures and can easily be extended to custom functions. Please refer to the Jinja2 documentation to get an overview about its features and handling. Any template files related to the jinja2 renderer are located in the folder html/ within the project structure.

Let’s create two simple HTML templates to render the list of persons and to show one person entry. First, the listing template is stored as person_list.html into the html/-folder.

{% extends "index.html" %}

{% block content %}

<ul>

{% for skel in skellist %}

<li>

<a href="{{ seoUrlForEntry("person", skel) }}">{{ skel["name"] }}</a> is {{ skel["age"] }} year{{"s" if skel["age"] != 1 }} old

</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

{% endblock %}

Then, the single entry viewing template is stored as person_view.html into the html/-folder.

{% extends "index.html" %}

{% block content %}

<h1>{{ skel["name"] }}</h1>

<strong>Entity:</strong> {{ skel["key"] }}<br>

<strong>Age:</strong> {{ skel["age"] }}<br>

<strong>Created at:</strong> {{ skel["creationdate"].strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M") }}<br>

<strong>Modified at:</strong> {{ skel["changedate"].strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M") }}

{% endblock %}

To connect the Person module from above with these templates, it needs to be configured this way:

from viur.core.prototypes import List

class Person(List):

viewTemplate = "person_view" # Name of the template to view one entry

listTemplate = "person_list" # Name of the template to list entries

def listFilter(self, query):

return query # No filters: everyone can see everything!

But how to call these templates now from the frontend? Requests to a ViUR application are performed by a clear and persistent format of how the resulting URLs are made up. By requesting https://hello-viur.appspot.com/person/list on a ViUR system, for example, the contents from the database are fetched by the Person module, and rendered using the listing template from above. This template then links to the URLs of the template that displays a single person entry, with additional information.

#TODO: [screenshot follows]

So what happens here? By calling /person/list (or just /person) on the server, ViUR first selects the module person (all in lower-case order) from its imported modules and then calls the function list, which is a build-in function of the List module prototype. Because no explicit renderer was specified, the HTML-renderer jinja2 is automatically selected, and renders the template specified by the listTemplate attribute assigned within the module. Same as with the viewing function for a single entry: ViUR first selects the person module and then calls the build-in function view. The view function has one required parameter, which is the unique entity key of the entry requested.

You can simply attach other renders to a module by whitelisting it.

from viur.core.prototypes import List

class Person(List):

viewTemplate = "person_view" # Name of the template to view one entry

listTemplate = "person_list" # Name of the template to list entries

def listFilter(self, query):

return query # No filters: everyone can see everything!

Person.json = True # grant module access to json renderer also

If we granted module access also for the json renderer above, the same list can also be rendered as a well-formed JSON data structure by calling https://hello-viur.appspot.com/json/person/list. The json as the first selector in the path selects the different renderer that should be used.

ViUR has a build-in access control management. By default, only users with the “root” access right or corresponding module

access rights are allowed to view or modify any data. In the module above, this default behavior is canceled by overriding

the function listFilter.

It returns a database filter for list function.

If None is returned, access is denied completely. Otherwise ViUR will only list entries matching that filter.

As we just return the incoming filter object, information of this module can be seen by everyone.

Any other operations, like creating, editing or deleting entries, is still only granted to users with corresponding access rights.